Only 7% of the Scottish population regularly attends church (2017 statistics). Scotland has not always been like this. Christianity most likely came to Scotland through the Romans. Back then it was known as Caledonia. The Romans invaded in 83AD being victorious in a battle near Aberdeen with Scots who were then known as the Picts. They built a series of forts for 50 miles North of the Firth of Forth. In the decades to come they further consolidated their stronghold by building the Antonine wall North of Glasgow. The Romans pushed into Caledonia in 209-210AD to subdue a ‘Scottish’ rebellion. Emperor Severus sent an army of 50,000 men, the largest Roman force ever to touch down in the British Isles. Christianity had gathered a foothold most likely through these invasions. The Christian scholar Tertullian, writing in or about the year 208 AD describes the spread of the Gospel in Europe as follows. “In all parts of Spain, among the various nations of Gaul, in districts of Britain inaccessible to the Romans but subdued to Christ, in all these the kingdom and name of Christ are venerated.”

Another Christian scholar Origen, in 239AD, wrote “The power of the Saviour is felt even among those who are divided from our world, in Britain.”

It is almost certain that disciples of Jesus who had breeched the first century, Roman Army as early as 41AD (with the baptism of the Centurion Cornelius Acts 10), converted men and women in the tribes living in what we now call Scotland, on the fringes of the Roman empire, in the early centuries even when the church was in its most primitive form.

Another in-road to the evangelisation of Scotland was through Ireland. It is believed due to the writings of the English historian Bede, that the Irish missionary Ninian (understood to be a spiritual descendant in the movement of St. Patrick) established a Celtic Church centre in Whithorn, at the end of the fourth century. The oldest christian document in Scotland found to date is estimated to be as early as the mid 400s. This fifth century Kirkmadrine stone 6 km south from Stranraer (and 15 miles west of Whithorn), carries a six line Latin inscription commemorating three bishops, Ides, Viventius and Mavorius, and reads ‘sancti et praecipi sacerdotes’, ‘holy and outstanding priests’. Another pillar stone, dated to around 600, carries the inscription ‘Initium Et Finis’, which translates as ‘the beginning and the end’.

St Colman’s church at Portmahomack is believed to be the earliest Pictish church found to date and estimated to have been built around 600AD nearly 30 miles north of Inverness and very much in ‘Highlander’ country! Other artefacts on display at Kirkmadrine include five stone cross fragments, dated to between 700AD and 1100AD.

Aside from the churches that met in large permanent buildings and organised with priests and finance to provide adjoining graveyards, like the ones at Kirkmadrine, Whithorn and Portmahomack, we know from both the biblical record of the early church and the copious history of movements of Christians all over the world, that there were believers active in spreading the gospel in more itinerant manners. In biblical times, first the believers met in the Temple (Acts 3:1, 21:26) and then further afield at Synagogues (Acts 18:26) and then in the large homes of wealthy members (Acts 16:13-15, 28:30) and in similar fashion throughout the centuries both in these places and in more remote places like forests, rivers or among the mountains. These groups often left no buildings or carved stones. There is therefore no reason not to believe that Orthodox Christians were living in Scotland from the earliest times.

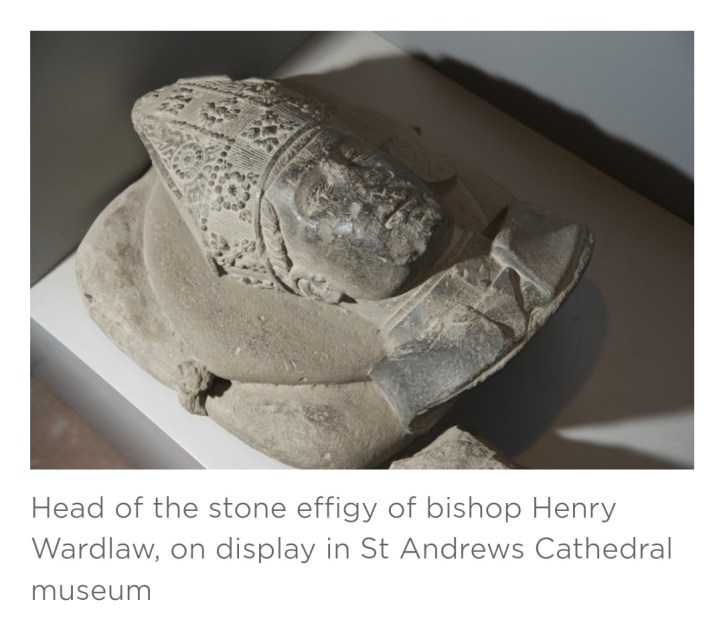

In 906AD, the town of St Andrews near Dundee became the seat of the Roman Catholic bishop of Alba. The Normans built the Cathedral in 1160AD making it the central point of pilgrimage in Scotland. On 23rd July 1433, Pavel Kravař, a physician from overseas, was burned at the stake in St. Andrews for heresy. He was a Checz-born immigrant, an ‘Anabaptist’ Hussite who had also lived in the south of France which was an area very alive with evangelicals. Pavel had graduated as a Bachelor of Medicine in Montpellier in 1415 (where also one Catherine of Thou entered a closed convent as a nun in 1416 and subsequently converted the nuns therein and was burnt for her faith in 1417 by the catholic inquisition). We see that Pavel had opportunity therefore to have been influenced by Waldenses active in the south of France who had the same salvation teaching as the Bohemian Hussites in Prague. The Hussites had ‘heretical’ ideas, which included: The Church should not amass wealth, the Word of God should be preached freely and non-leaders should receive both bread and wine at Communion. The more radical Hussites went as far as to claim that saints, pilgrimage and monastic life had no basis in the Bible. In May 1516 Pavel was among the members of the faculty of Charles University in Prague and became a follower of the Hussite doctrines. From 1421 Paval was in Poland as a royal physician. In 1433 under unknown circumstances, he travelled to Scotland and began to preach his convictions at St. Andrews. He would have been well acquainted with university campus ministry and reaching out to academics after his experiences in Paris and Prague. Pavel was arrested by bishop Henry Wardlaw. He met the Scottish inquisition! He was convicted of heresy and burned at the stake and a blue plaque was only displayed in his honour in 2016 at the place where he was executed. It is not known whether or not he was able to convert any individuals before his death. It is unlikely that he was stupid enough to preach publicly when he first began his ministry in Scotland after having been in multiple situations where his convictions were resulting in executions.

In the decades prior, in England, noteworthy burnings included numbers of the clergy, who were deemed heretics by the Roman Catholic church for their beliefs regarding infant baptism and many other matters of Catholic doctrine that have been carefully recorded. Thus we see that in Scotland prior to the Protestant Reformation, believers lived and preached who were put to death for their faith.

The most prominent Scottish reformer was John Knox – he was was born in 1514 in Haddington approximately 15 miles east of Edinburgh. He was a disciple of John Calvin, a believer in the total depravity of mankind and he is regarded as the notional founder of the Presbyterian church which was established 120 years after his death. He wrote two papers of note that outrightly condemned Anabaptists as heretics, who had identical beliefs to Pavel Kravar and who were executed in their thousands all over Europe by both Catholics and Protestants between 1519 and 1660.

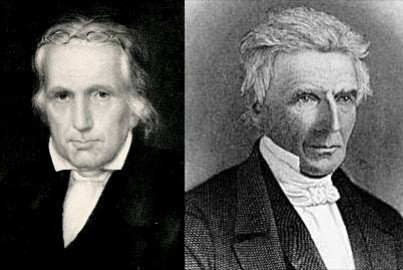

Ulster-Scottish, father and son, Thomas and Alexander Campbell were the founders of the ‘Restoration Movement’ in the 1820s in the United States of America. Thomas was a Presbyterian Minister who left Scotland for America in 1807. He became disillusioned with Protestantism believing that rather than bringing the Catholic Church back to the righteous life and spreading of the gospel, it had only served to further divide believers. Together with a group of like-minded former members of the Methodist church, they formed the Restoration Movement which by 1900 numbered three million members and had planted at least a dozen congregations back in Scotland.

Today the mainline churches of Christ are in decline. Attempts at revival in the ICOC movement that came from the Churches of Christ in the 1970s through to 2003 have faltered. It is therefore time for disciples to once again take up the challenge of the evangelisation of Scotland in our generation.

On 23.1.22 we extended the warmest of welcomes to our first official church service – the inaugural service of the Edinburgh International Christian Church!