1 Timothy 2:3-4

This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all men to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth.

When considering the evangelisation of the African continent in the first century, a useful starting point is to examine the records in the New Testament, with particular focus on how the Roman world and other empires with widespread literacy were evangelised. The conversion of the Apostle Paul in 37 AD stands as a pivotal event, as he was specifically chosen as the Evangelist to the Gentiles, particularly in Asia Minor and Europe. His missionary journeys are well-documented, providing a clear picture of his movements and strategy.

Paul, first and foremost, was a Pharisee with extensive knowledge of the Scriptures. He was highly literate, educated by renowned scholars, and, crucially, a Roman citizen. This granted him the ability to travel freely within the Roman Empire, utilising its well-developed road networks, and the shipping lanes and infrastructure. His strategic approach involved first preaching to Jewish communities, converting those already literate in the Scriptures, before expanding his mission to the broader Gentile population.

Additionally, Paul’s background in Tarsus—a Greek-speaking city—meant that he was well-acquainted with the apologetics used by Jewish communities when engaging with Greek intellectuals. His ability to navigate both Jewish and non-Jewish audiences made him uniquely suited for the task of spreading Christianity. Furthermore, historical analysis shows that the Roman world of the first century was remarkably centralised and technologically advanced, facilitating the rapid and widespread dissemination of the Gospel message.

Beyond Biblical sources, the archaeological evidence for the events and prominent converts described in the New Testament in the first century remains scarce. Even the bones of martyrs who died for their faith cannot be distinguished from those of the other people alive at the time. While some literary sources provide historical corroboration for figures mentioned in the New Testament, physical evidence of early house churches is extremely limited. In Rome, for instance, the Basilica of Saint Clement, situated behind the Colosseum, stands as an example. Beneath the modern Bacilica is a basement with a medieval church, and even deeper, a subterranean level said to contain the house of Clement (Phil 4:3), an early leader of the church in Rome following the Apostle Paul’s martyrdom. However, this consists of mere ruins of a domestic dwelling, and while certain sites in Rome have been traditionally identified, definitive proof remains elusive.

Thus, while the evangelisation of the Roman world is well-documented, it lacks a comprehensive body of direct archaeological evidence pinpointing specific locations where particular disciples preached. Many such identifications are based on historical reconstructions and best estimates, rather than irrefutable proof. Later institutions, such as the Roman Catholic Church, have relied on tradition to assert knowledge of certain locations, yet a thorough scholarly examination reveals that absolute certainty is often unattainable. Nonetheless, the historical reality of early Christian expansion is undeniable.

Turning to the evangelisation of Africa, the same Holy Spirit that guided the spread of Christianity through the Roman Empire was undoubtedly at work beyond its borders.

Even in the Persian Empire, there is clear evidence that evangelisation was taking place from the very beginning of the early Church (Acts 2:7-11). As I have previously explored in my article on Novatian, Christian missions extended far beyond the Roman world, with early believers carrying the faith to lands both within and beyond the empire’s reach including China.

The Chinese Churches

In 2002, Wei-Fan Wang conducted a study and subsequently published photographs of reliefs from tombs built during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD). These reliefs depict scenes that are representations of the Nativity, including the Magi, as well as Satan as the dragon lurking to seize the child. Additionally, they feature the Garden of Eden narrative, with Satan and Eve taking the fruit from the Tree of Life. Wang also discovered a bronze plate adorned with imagery of two fish and five loaves, an apparent allusion to the well-known biblical account of the Feeding of the Five Thousand.

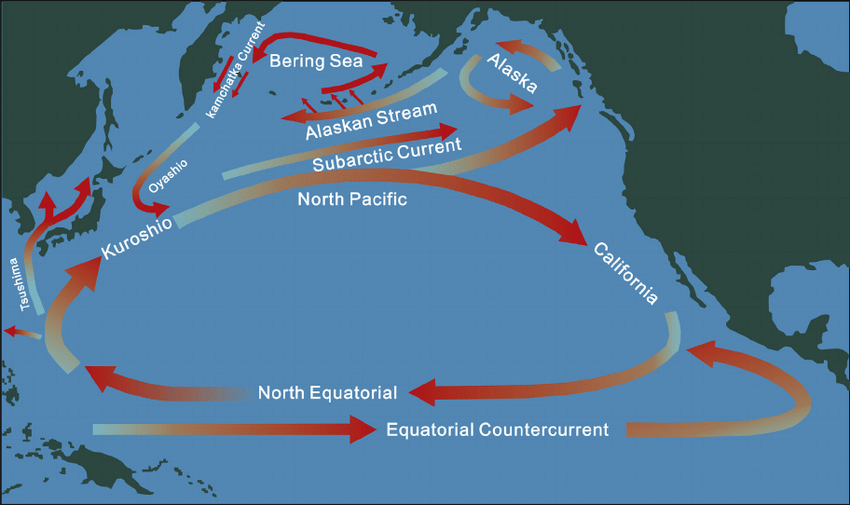

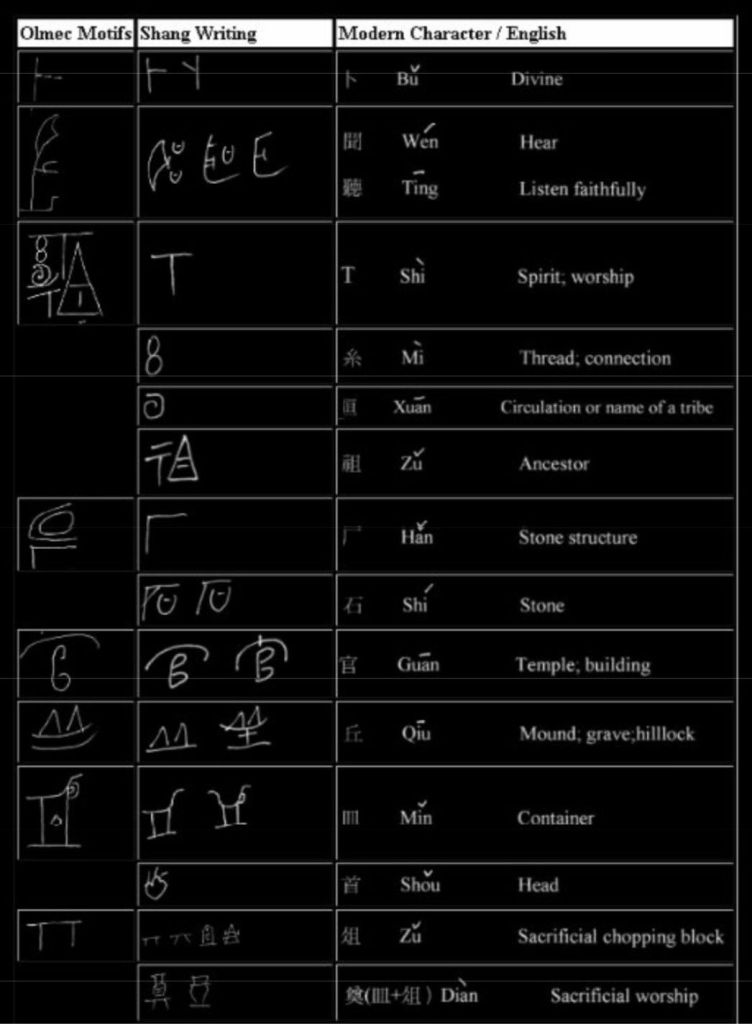

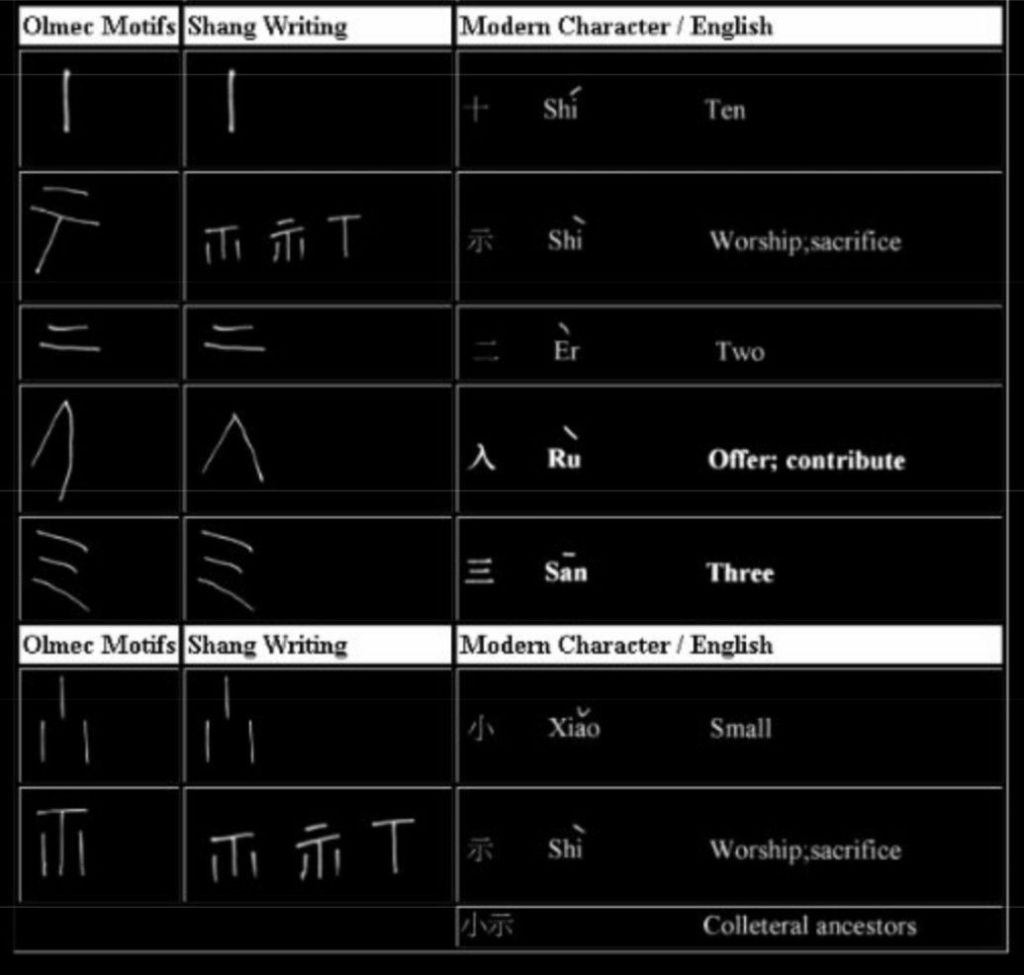

At that time, the Eastern Han Dynasty possessed a formidable navy, with sea-going vessels capable of undertaking long-distance voyages. Given this, it is not only plausible that China was evangelised in the first century, but also conceivable that Chinese disciples of Christianity had the maritime capability to spread the gospel across the Pacific to the Americas. Furthermore, archaeological evidence shows that the earlier Chinese Shang dynasty had contact of some kind with Central American civilisations as early as 1000–900 BC most likely via the north Pacific current that flows from near China to Mexico. The list of writing symbols discovered in both countries shows undeniable similarity between the systems in China and Mexico (see below). China has an old legend that speaks of many members of that society going ‘missing’ during the 600 years of the Shang dynasty. There does not yet appear to be pictures online of the symbols of multi-oared ships on Shang reliefs but researchers have documented their existence.

The Liye Qin Slips (里耶秦简) are another collection of ancient wooden and bamboo slips, discovered in 2002 in Liye, Hunan Province, China. These texts, dating back to the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC), primarily contain administrative and legal records. However, among these documents, certain passages show that Christian doctrines and monotheistic beliefs were already known within segments of Chinese society during this early period.

The “Heavenly One” Slip references a singular, supreme deity governing all things.

The “Moral Law and Righteousness” Slip outlines ethical principles emphasising justice, integrity, and truthfulness.

The “Life After Death” Slip alludes to an afterlife and posthumous judgment, concepts not traditionally prominent in Qin-era ideology.

The “Light and Darkness” Slip employs metaphors of light and darkness to describe moral duality, a theme reminiscent of biblical teachings.

The “Messianic Figure” Slip speaks of a prophesied ruler who will bring harmony and justice, described as a singular, righteous leader destined to restore balance.

Again, coming back to the first century evangelisation of Africa, it is both informative and interesting to consider that the academic world (including modern Chinese intellectuals) continue to be sceptical of the growing body of evidence, pointing to primitive Christianity in China in the first century, preferring to look to the arrival of Roman Catholics centuries later as the advent of Chinese Christianity. So we see that the spread of the disciples of Jesus that happened very obviously within the Roman empire (and was falsified by Constantine by the 300s), was paralleled in the Persian Empire and in China (who had the technology at that time to spread it Eastward to the Americas or even South to Australia). So now that we’ve looked at the rest of the planet let’s turn our attention back to Africa.

The Ethiopian Eunuch and the Spread of Christianity in Africa

It was an Igbo Nigerian man who originally studied the Bible with me in 1990. In the 34 and a half years since my baptism, I have probably taught from Acts 8:26 onwards hundreds of times and have certainly sat in studies with others teaching from the same passage at least several hundred times. This passage tells the well-known story of the Ethiopian Eunuch, the only black African man explicitly documented as being baptised in the Bible.

In many of these studies, the teacher—including myself—has estimated the distance and duration of the journey from Addis Ababa to Jerusalem. According to Google Maps, the route would take 39 days to walk one way. However, the Ethiopian Eunuch travelled by chariot, pulled by horses, which would have made his journey significantly faster.

The distance by road between Addis Ababa and Jerusalem is 2,638 km. If his horse-drawn carriage averaged 80 km per day, then a round trip would have taken approximately 65 days. If he stayed in Jerusalem for a few days, the total journey could have lasted around 70 days, meaning he would have had to take at least two months off work as treasurer to the queen in order to complete it.

Over the years, I have heard a wide range of estimates for the length of this journey, ranging from a few weeks to six months.

Where Was the Eunuch From?

The man we call the Ethiopian Eunuch was converted sometime between 33–36 AD, based on the dating of the Apostle Paul’s conversion in 37 AD. He served as treasurer to Queen Nawidemak of Meroë, a ruler of the Kingdom of Kush (modern Sudan).

Acts 8:26-29 Now an angel of the Lord said to Philip, “Go south to the road—the desert road—that goes down from Jerusalem to Gaza.” So he started out, and on his way he met an Ethiopian eunuch, an important official in charge of all the treasury of Candace, queen of the Ethiopians. This man had gone to Jerusalem to worship, and on his way home was sitting in his chariot reading the book of Isaiah the prophet. The Spirit told Philip, “Go to that chariot and stay near it.”

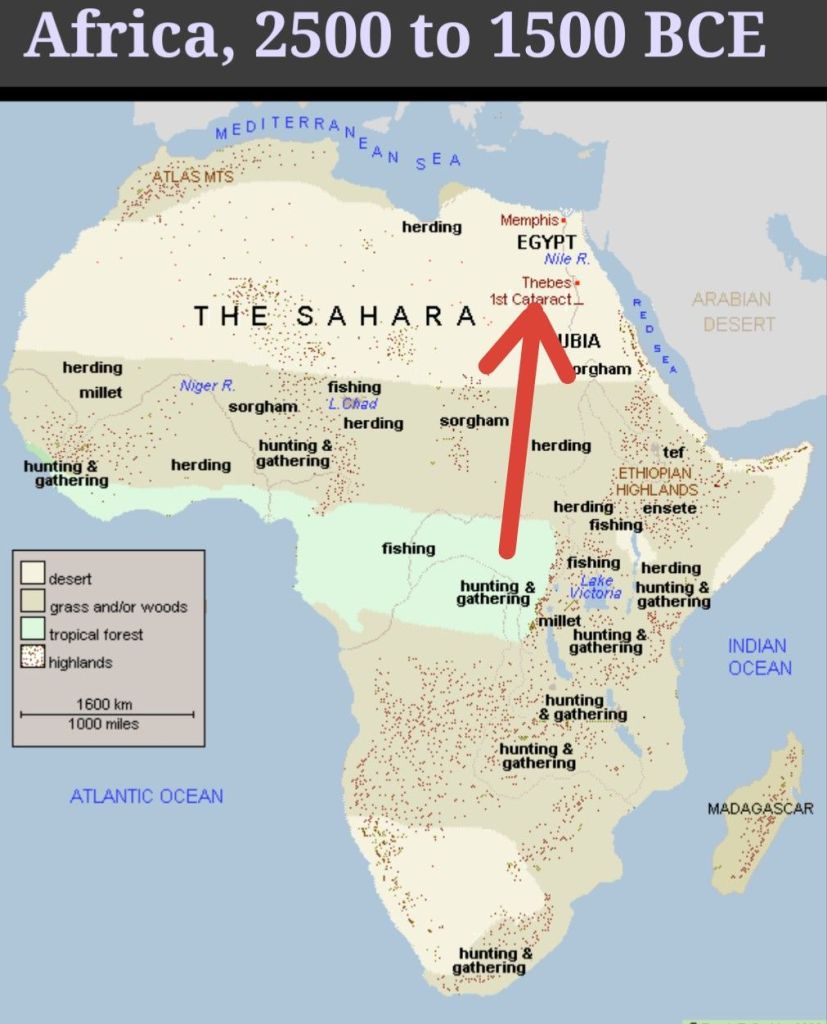

For the last three decades, I mistakenly believed that the Ethiopian Eunuch was from Ethiopia. The Greeks and Romans were well aware of the region known as “Ethiopia”, though their understanding of the term differed from the modern nation of Ethiopia. In ancient Greek and Roman sources, the word “Aethiopia” (Αἰθιοπία) referred broadly to the lands south of Egypt, which included Nubia (modern Sudan), Ethiopia, and other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. It is no surprise, then, that the Eunuch was a Kushite rather than a modern Ethiopian. Most eunuchs in royal courts were enslaved in childhood. The history of the region tells us that slaves were trafficked into Kush from other parts of Africa. One example of this is found in the inscription of Harkhuf (2290 BC), an Egyptian official who described his journey to Yam, a distant land south of Egypt, from which he brought back a dancing pygmy (dwarf) for Pharaoh Pepi II or Pharaoh Merenre I.

Harkhuf’s expedition to Yam took seven months in total (three and a half months each way). The estimated distance ranged from 1,500 km to 3,000 km, which suggests that he may have travelled as far as Chad or Central Africa via the Sahel corridor. Today, Pygmy tribes in Cameroon and the Central African Republic still maintain strong dance traditions, which may indicate that the dancer Harkhuf transported came from the same region—4,100 km away from Egypt.

This historical precedent proves that slaves and officials could be transported halfway across the entire African continent as early as 4,000 years ago, meaning that our Ethiopian Eunuch from only 2000 years ago, if originally enslaved, could have been from almost any part of Africa.

A Highly Literate and Cosmopolitan Figure

The Eunuch was undoubtedly a highly intelligent and well-educated man. He was at least bilingual, fluent in Greek and Meroitic, and possibly acquainted with Hebrew or Aramaic, given his journey to Jerusalem. The passage he was reading in Acts 8:32-33 is almost identical to the Septuagint (LXX) version of Isaiah 53:7-8, rather than the Hebrew Masoretic Text, indicating that he had access to Jewish Scriptures in Greek.

His cosmopolitan identity is similar to that of Paul of Tarsus. Paul was both a Jew and a Roman citizen; the Eunuch was both a black African and a Kushite believer in Yahweh. Both men were highly literate, educated, and well-connected.

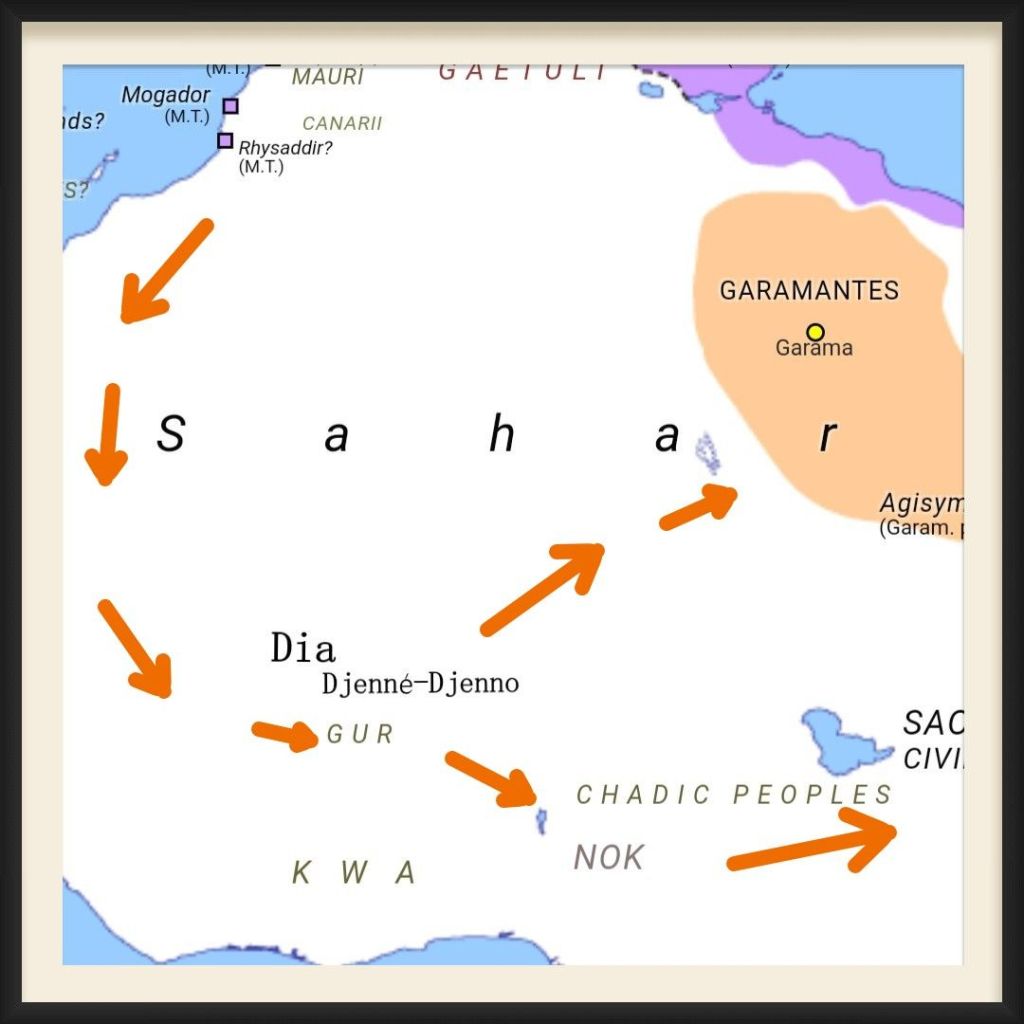

As the head of the treasury, the Eunuch would have personally known the key figures involved in the trade routes linking Kush to Sudan, Chad, and Mali. He may have been aware of the Roman expeditions into Africa, such as the expedition of Lucius Cornelius Balbus into North Africa in 19 BC, as part of his education. In the first century, below the borders of the Roman Empire in the North African Mediterranean, in what is now the South of Algeria and Libya lived a tribe called the Garamantes that were a racially stratified society with Berber, Black African and mixed sections of their society. They had inhabited this region since at least 1000 BC. They were involved in the human trafficking of slaves and goods from the Sahel area and also had members of their society from the Sahel (most likely added as slaves, although some rose to higher rank possibly via marriage). Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, references the expedition of Lucius Cornelius Balbus into North Africa in 19 BC and the defeat and subduing of the Garamantes. Roman coins found in the Sahel suggest that parts of this campaign continued further south to gather intelligence and seek out the sources of natural resources that were being traded into the Roman Empire. A subsequent 41 AD campaign down the West of Africa over the Atlas mountains and beyond probably happened within the Eunuch’s career.

He was most likely also aware of the 50 AD campaign of Septimius Flaccus, which reached Lake Chad, further expanding Rome’s knowledge and control of the ancient trade routes and the 58–63 AD campaign of Nero’s general Strabo, which involved further Roman expeditions into the Sahara to subdue the Garamantes. If the Eunuch’s ministry lasted as long as Paul’s (37–68 AD, about 31 years), he would still have been alive during these later campaigns and aware of Rome’s growing influence over the trans-Saharan trade routes.

The Trade Routes Across Africa

In the first century AD, the Sahel trade routes extended across the entire African continent. Archaeological discoveries confirm that trans-continental trade was flourishing in regions such as Mali, 2,500 miles south of North Africa. For example: At Dia (an ancient trading city in Mali), archaeologists have found red carnelian beads, indicating that trade was flowing westward from Egypt or India via Kush and across the Sahel corridor.

At Djenné-Djenno (near modern Burkina Faso), the Mande and Bozo peoples were trading with the Garamantes from at least 250 BC to 900 AD.

These findings prove that Africa was already well connected by trade routes in the first century, at the time of the Eunuch’s conversion in 36 AD. As discussed earlier, it can be understood that the practice of slavery in Africa as far back as 2200 BC, shows that even tribes that had technology to aquire and refine natural ores, but no evidence of transportation and trading of their natural resources (such as the Nok culture of Nigeria) could easily have been in contact with the trade routes through the slave trade. The Bantu people’s originating from Cameroon 2000 BC and spreading all over central and south Africa could have been reached via similar trade routes as they interacted with Yam and Kush via migration. If the Pygmys were on the map 4300 years ago why would not the San aboriginals (bushmen) also have had a chance to know the gospel via the Bantu peoples? All this would have only required several more similar men or women of antiquity like Dibi to have been converted a thousand miles apart to close the loop. We have to remember the unique circumstances of the Eunuch’s conversion. He was on a 5000 km round trip. Why would any disciple lack the faith to say that this was God’s chosen method for the evangelisation of the African continent as well as the far East and the Americas. The Eunuch is the main Archetypal clue as to how the evangelisation of the world occurred in the first century so that Paul could write;

Colossians 1:23 “This is the gospel that you heard and that has been proclaimed to every creature under heaven, and of which I, Paul, have become a servant.”

(Incidentally, it was also through Caucasian slavery that my country was evangelised – Patrick was a Briton slave in Ireland!)

Compare the long distances travelled in ancient Africa to what we know about Otzi the iceman who lived in Northern Italy around 3,300 BC. Our scientists have been able to confidently tell us he was a trader and was murdered at high altitude and that he had weapons/tools that were made at least 500 km away from the Alpine valleys he lived in over his lifetime. He died at a very high elevation (above 3200 m) in the permafrost of the Alps wearing high-tech weather gear and carrying a medical kit and a lot of equipment! The scientific community can imagine a lot with the Caucasian ancients so we should equally be able to extrapolate the data we have to show whether or not the world was evangelised in the first century. One very important thing to bear in mind is that most people in the world today have not read enough of the bible to understand that primitive Christianity would not have left behind anything for archeologists and genetic scientists!

The Eunuch’s Role in the Spread of Christianity

I will call this man Dibi, after the finance minister of Côte d’Ivoire when I preached there about the Eunuch in 2012.

Dibi had access to the Septuagint in Kush and likely belonged to a Jewish faith community.

He had a queen (Nawidemak) who was sympathetic to his religious views. Below are the pictures and location of her tomb.

He had access to the vast Sahel trade network and the intelligence that the region was increasingly coming under Roman control.

Like Cornelius, the Centurion (converted in 41 AD), Dibi likely had attendants, possibly former slaves, who he may have also converted.

He may have had ties to his homeland and connections to trade routes that extended deep into Africa.

His intellect, influence, and access to powerful networks made him an ideal candidate for spreading Christianity across Africa. Given his understanding of Scripture, it is possible that he already suspected he had a divine purpose, much like Esther in Persia.

How can we not consider Dibi to be one of the most important figures in the spread of Christianity across Africa? Did the Holy Spirit not desire the salvation of all African men?

For too long, Western education and colonial thinking have led me to underestimate the extent of Christianity’s spread in Africa during the first century. However, archaeological and historical evidence show that it is entirely possible that the Gospel reached the whole continent within decades of Christ’s resurrection! Come the moment, come the man.